Once upon a time in Grámmata, Medellín

Author: ©2025 William Castano-Bedoya

“THREE-MILES CHONICLES” “Sometimes a single occupied chair is enough for literature to feel at home.”

I walked early this morning. The sun was barely touching the streets of Coral Gables when I found myself thinking again of Medellín, of the Grámmata hall, of the empty chairs waiting for readers. My own people came—the ones I had invited.

To Grámmata, my gratitude for welcoming me that night.

And yet, that image—the half-filled room—accompanied me throughout my walk today, like an honest mirror: literature, too, is measured by its silence and by the solitude of those who write it.

I pondered many things. Medellín, a city of readers and creators, vibrates with an energy I deeply admire, even if that night the readers were not waiting for me. It does not sadden me; it makes me aware of the reality we live in—those of us who write far from the noise and the display windows.

There are nights that do not fill up, and that too is a kind of truth.

What remains, beyond attendance, is the dignity of continuing to search, of keeping the word alight.

Rooms only fill when the conspiracy of discovery lights the path toward new readers.

There is no resentment, only resignation—and a grounding humility that keeps me steady.

Everything is real.

Our universe—the one of independent writers—is made of genuine voices, often invisible, yet necessary.

We live in a world saturated with words, where few still manage to awaken wonder.

I will keep writing and sharing my work—who else would do it if not me?

Perhaps Medellín will wait for me in other lines;

perhaps someday it will read Ludovico, the most paisa of all my characters, or The Beggars of the Mercury Lights, The Galpon, Flowers for María Sucel, We’ll meet in Stockholm, or any other novel I am writing now.

A few copies of my books remain on display at Grámmata, for those who might stop by, leaf through them, and—why not—read them. It will be an act of personal fulfillment rather than an existential offering: the joy of knowing my books dwell in a place where, at every hour, literature is in the air.

That day, I will not need a full room; a single listener will suffice.

And still, the melancholic tone of my morning walk led me to one conclusion: miracles do happen.

That night in Grámmata turned into magic. The full house was no longer necessary; one chair was enough—occupied by a simple woman, dressed in red, and her son. They were there when I entered the hall. Some people were drinking coffee, and a local poet approached me to show a beautiful book published by the same bookstore. We exchanged a few words—we were already absorbed in the conversation with my interviewer. I hope I wasn’t inattentive; I assumed we would speak later about her work. Everything unfolded under the pressure of time, and my priority remained the dialogue with Arbey.

I noticed that the poet didn’t stay for the talk; she just sipped her coffee and mingled. Little by little, everyone left. No one sat down. That evening, the parche wasn’t meant to accompany my conversation. And I understood—it was natural, part of the same chance that governs words. There was no disappointment, only the quiet acknowledgment of the ephemeral.

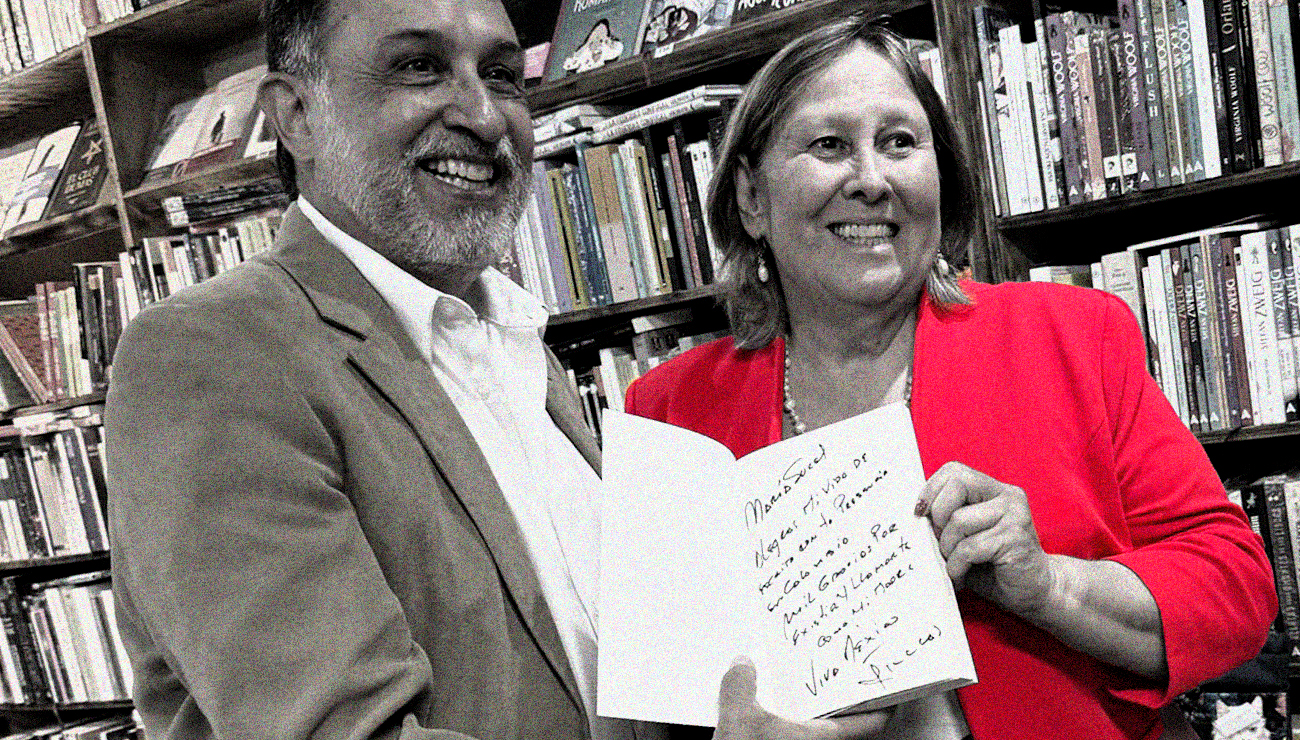

While rehearsing the questions my interviewer, Arbey Salazar Blandón, had prepared, the woman in the red dress approached me and said:

—My name is María Sucel.

—María Sucel? —I replied, surprised.— What an unusual name… I only know the one from my novel.

She smiled.

—My last name is Flores. I’m María Sucel Flores. I came to buy your novel and have you sign it.

My novel is titled Flowers for María Sucel.

I was speechless. It felt as if the pages themselves had risen from the book to thank me. When I asked if she was from Medellín, she told me she had traveled all the way from Hermosillo, Mexico, just to meet me and buy the novel. She said her son had given her that trip as a gift and that she had found me through the posts we shared on social media.

At that moment, I felt illuminated—undeserving, grateful. And I don’t exaggerate when I say that, amid that profound solitude, I felt the room completely full and my heart expanded. I wanted to embrace her, as if something cosmic had descended toward me: the fantasy of the miracles literature can create. Only I could feel that astonishment, that gratitude.

The locals didn’t come—not even a small sample of the faithful audience that usually inhabits that sacred space. And yet, one single visitor—with Mexican blood and Aztec soul—filled the night with grace. Someone said to me, by way of consolation:

—The night is saved.

I asked María Sucel to sit before me, because the first thing I did was to recognize her effort before those who had accompanied me: close friends and family. No one outside our intimate circle—only that Mexican woman who had crossed thousands of miles in search of me. I signed her book by hand, with the pride of one who frees his story into the firmament of writers. When I spoke to the audience about that coincidence—about María Sucel made flesh—I invited her to one of the events we’ll hold to celebrate the twentieth anniversary of that novel. We don’t yet know where it will be—perhaps in some city of Latin America, or in the United States; maybe in Hermosillo, Mexico, why not? But I’m certain it will be another act of encounters and miracles.

The minutes slipped by in a beautiful conversation. Arbey led the interview with the patience and care of someone who truly prepares a conversation with a writer. I enjoyed every one of his questions. His reading, his genuine interest, his respectful curiosity about my characters were the true prize of that evening. My thanks to him—for listening, for asking, for making the dialogue worth more than the number of chairs filled. During our conversation, Arbey asked about a person I hadn’t seen in half a century, someone he had found mentioned in the academic material I carry with me: Luis Fernando Parra Gallego, a teacher born in Marinilla, who, in the Bogotá of the seventies, conquered the classrooms with his wisdom in philosophy and letters—a man admired and revered by all of us who were his students.

Unknowingly, he was the one who introduced me to The Life of Lazarillo de Tormes and to the irrevocable destiny of literature, when I was still a high-school student in a small corner of that city.

That question surprised me.

I have always evoked Luis Fernando as my literary mentor through every stage of my life—the one who, in our youth, infused us with his wisdom and his love for letters.

They were marvelous years, filled with conversations, readings, and literary bohemia. Life, as always, eventually cast us into its currents and silences. The miracle was that a few days later—already back in the United States—I managed to find him. He is retired now; his vocation led him to become a priest, and he spends his years of rest in Rionegro, Antioquia. I will surely visit him soon, and we’ll speak of those inspiring days. To know he still exists is, for me, another miracle born in Grámmata.

As I walk, I ponder the gratitude I feel for my anonymous readers—those who once wrote to me without name or signature, saying: “Your book didn’t change my life, but it kept me company while mine was falling apart.” And I think too of those who drifted away—those who grew weary of my insistence, of my stubborn faith in the word. They too taught me the value of silence.

I will keep searching for readers brave enough to discover my lines, my arguments, my characters— without the guidance of algorithms or the push of fashion. I expect no more than what already is. I cannot speak of crowded rooms; such things do not exist in my universe. But I can say that friends accompany me in letters, in readings, in stories shared. In my work there is truth, faith, and gratitude.

I know I belong to that invisible army of writers who keep writing, even if no one names them. And that, far from saddening me, defines me. Because writing today is an act of faith—but also of resistance. Faith that there are still souls willing to read slowly. Resistance against a world that celebrates noise and forgets the word.

And then I understood: the emptiness of readers in Medellín taught me more than any applause ever could. That city vibrates in other latitudes—in its joyful tourism, its overflowing creativity, its love for what is beautiful and immediate.

Medellín owes me nothing. I, on the other hand, brought everything back: its generosity, its pulse, its good people—so alive, so enthusiastic.

Because miracles, I now know, do not fill rooms.

They fill the soul.

Your next favorite story is just one click away.

Explore my novels here.

The Sky Also Belongs to the Beggars

Once upon a time in Grámmata, Medellín

A Planetary Choreography: Each Tragedy Serves as a Screen to Hide Another

William Castaño

William is a Colombian-American writer who captivates readers with his ability to depict both the unique experiences and universal struggles of humanity. Hailing from Colombia’s Coffee Axis, he was born in Armenia and spent his youth in Bogotá, where he studied Marketing and Advertising at Jorge Tadeo Lozano University. In the 1980s, he immigrated to the United States, where he naturalized as a U.S. citizen and held prominent roles as a creative and image leader for projects with major corporations. After a successful career in the marketing world, William decided to fully dedicate himself to his true passion: literature. He began writing at the turn of the century, but it was in 2018 when he made the decision to make writing his primary occupation. He currently resides in Coral Gables, Florida, where he finds inspiration for his works. William’s writing style is distinguished by its depth, humanity, and authenticity. Among his most notable works are ‘The Beggars of Mercury’s Light: We the Other People’, ‘The Galpon’, ‘Flowers for María Sucel’, ‘ Ludovico’, and ‘We’ll meet in Stockholm”.