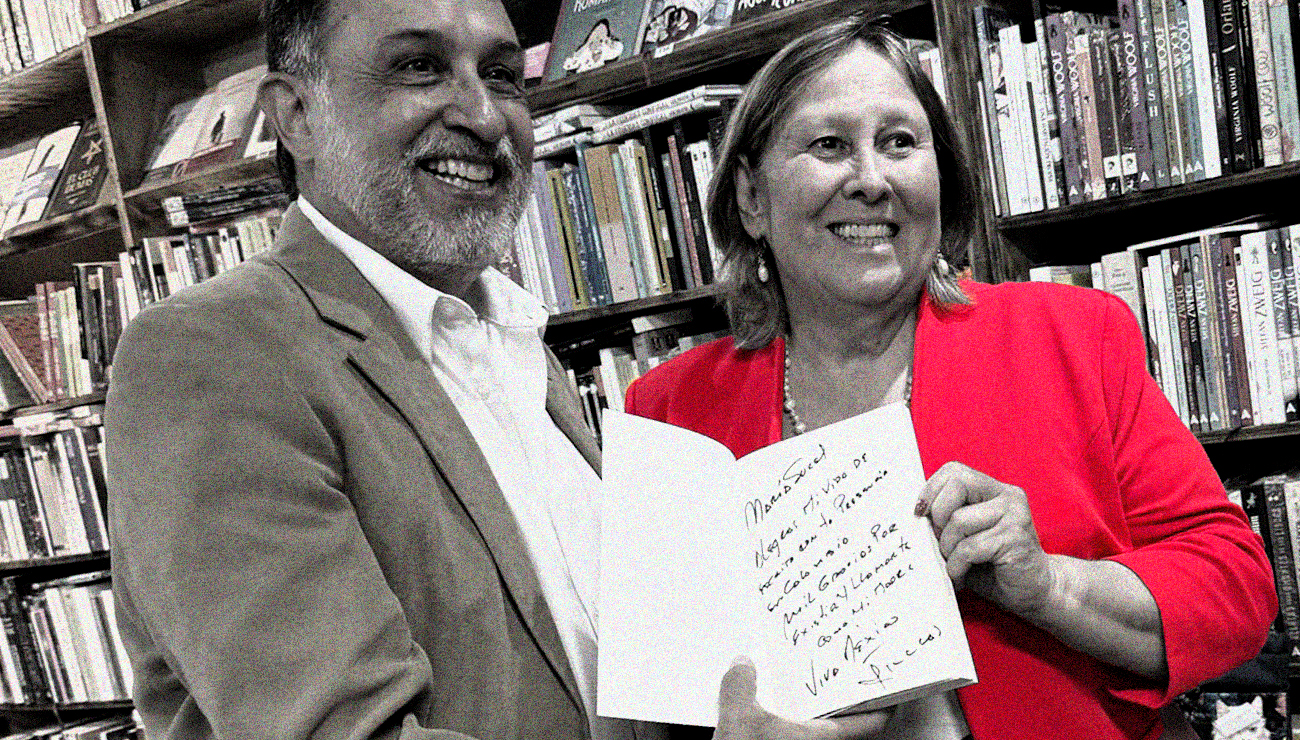

William Castaño-Bedoya, the Quindian writer who transforms exiles into literary works

“I may not be the best writer, but I feel what I write about,” William Castaño-Bedoya, who is from Quindío, states with some modesty. His novels are brimming with humanity, for when a subject gets stuck in his mind, he usually digs deeply into his characters to leave bare their complexity.

He did so with the novel he titled Flores para María Sucel, which is a fictional parody of his parents’ lives. After his mother’s death, he toured several towns of the Colombian coffee region to investigate his roots and write the novel.

His second book is a psychological fiction named The Monologues of Ludovico that resembles, to some extent, works such as Franz Kafka’s The Metamorphosis, or the short story Eyes of a Blue Dog, by Gabriel García Márquez. In this novel he tackles the complex inner world of a man from a well-to-do family, with a hereditary mental condition that brings him closer to the realms of the absurd. William has already finished adapting his novel for the stage.

He spoke with LA CRÓNICA from his home in Coral Gables, Florida, where he lives with his family.

What led your family to leave the city of Armenia for Bogotá when you were six years old?

My father was one of the founders of the El Paraíso neighborhood in Armenia, which is the capital of the Quindío Department in Colombia. From the gallery in Armenia, he managed the sale of grains in the region. My father’s downfall began due to several circumstances. I remember when I was very young, burglars emptied our house and my mother told me that he had a mistress and wanted to get out of that situation to salvage his home. He was from Antioquia, quite the chauvinist with his romantic escapades and habitual infidelities, mostly in the gallery where he kept himself surrounded by loose women and all sorts of fashionable things. This all created a certain instability. This I refer to as exiles of self; because my father was someone whose life’s woes caught up with him but instead of facing them and setting things in order, he preferred to run away and exile himself in evasiveness, in other lands, pulling away from his own surroundings to avoid exposure to the truth galloping from the lies. However, despite it all, he was a good man. When we arrived at the capital we lived in a very complex neighborhood. He was always a merchant, but had no luck there because some business associates who were supposed to make his meager funds into profit failed to do so and he slowly lost every penny. Out of eight siblings, there were five of us left, also my mother had an abortion without telling my father because she was tired of so many children in such poverty. In those years, like now, abortion was condemned by very traditional families and by the Catholic church. Abortion has always been clandestine in Colombia. The truth is that we arrived in Bogotá and were faced with tremendous poverty, and became part of the internal exodus that exists in Colombia. In any case, my father ran off because he was unfaithful and his affair put his family in danger and also because he was being threatened by criminals that had been creating a hostile environment regarding his finances. In Colombia, crime, the vaccine as they call it now, and robbing decent people, have always been a constant.

What were you searching for when you came to the coffee region to write your novel Flores para María Sucel after your mother passed away?

I had been living in the US for five years as a resident when my mother died in Bogotá due to medical malpractice. They had called me earlier to tell me she was in the hospital after having her pancreas punctured during a gall bladder examination. She died five days later; I was able to travel to Bogotá to see her, and maybe she felt my presence because she opened her eyes and bid me goodbye as she passed away at only 52 years of age, a young mother of eight. From the time I arrived at the clinic to find her intubated and sedated, her death took place in a matter of hours or minutes. From that time forward, I undertook to write about her life and my father’s life. I did not want it to be a terse biography, so chose to write a novel using the style and tone of great writers like García Márquez —who deeply researched his work like the excellent journalist he was—, I sought to copy him and do that research surrounding my family and their towns. I did that by going to Viejo Caldas seeking to find out about my grandparents and their parents’ lives, where they came from, where they were going, their customs and all the things that made them human, which is what has interested me. I made the trip in search of all that, but also seeking my inner self because I had left Quindío many years earlier, when I was only six years old, and that led me to travel through Manizales, Armenia, and Pereira. Now I visit neighborhoods in the Quindian capital, like Corbones, Quindío, and Granada, and they seem somewhat laconic to me, as if they were poised in time while maintaining the purity of their inhabitants. I was retracing my steps in that journey to reconstruct the story of my family’s third generation, which was my mother’s generation.

Has your inner circle ever included anyone with hereditary mental conditions like those of your novel’s character in “The Monologues of Ludovico”?

As I mentioned, I analyzed characters in Kafka and Gabo before shaping that character that I had been thinking about for many years, and that would address the universe of the absurd. In my immersion into the character, I also talked and consulted with psychologists in order to be able to approach the world of behavior, without their becoming similar to each other. My fears, with this fantastic character, was whether or not to address the issue of his sexuality, which I ended up doing because it’s also a part of their lives. According to my friend Sonia Gimenes, a Brazilian-American psychologist and author of the book Domestic Violence, How to Break the Cycle, edited by ECOE Ediciones, although he was about forty-four years old my character could possibly have the psychological development of a ten or twelve-year-old child, and his sexuality could nevertheless be like any adult because it obeys rather instinctive or innate stimuli. For years I also devotedly tracked characters like Ludovico, because close to the family there is a very beloved character who has a condition that is not autism or Down’s, but that is something relatively new in the scientific community, called “Fragile X Syndrome.” Although there is no scientific diagnosis that pigeonholes my character, there are profiles that make me think that his fascinating personality and his ethics of life fall into that condition. I have a very close Mexican friend in the United States who has a son with severe autism that makes him very aggressive, and to their endless emotional distress the family are forced to have him placed under special care. I have a Costa Rican friend whom I met on a flight from San Jose to Miami, whose children also share a similar condition. Another good friend, a Colombian, has a son with similar problems. They all deserve consideration and respect because their lives have been completely devoted to the care of their children with the hope of achieving improvements in their behaviors. These families suffer from hereditary genetic problems whose only hope is that life will go on, turning their suffering into happiness and their reasons for being. These are very courageous people whom I deeply appreciate and esteem. While writing the novel over a span of two years, at some point I thought I might call it When the Old Ones Die as a tribute to them, intensely thinking of the circumstances surrounding those like Ludovico who reach young adulthood or early middle age when the older people who care for them leave this world. The biggest concern of the parents of characters like Ludovico is to die before their children and leave them unattended. The Ludovicos that concern me in this novel are the ones who are still mental children at the age of fifty or even sixty, to whom losing their parents condemns them to total helplessness. I know there are Ludovicos who are alone in this world, who live in poverty, and I see them in the towns and cities of Colombia and in many countries I have visited.

I must clarify that everything that happens in Ludovico is psychological fiction and does not at any time represent real characters, but only the reality which I discern about them and the people who care for and love them. Howsoever it unfolds, fiction becomes a well-told reality. I created Ludovico as a character with no gray areas, it’s all either black or white in his concepts, the things that happen to him are either good or bad. Ludovico’s character is part of an economically affluent family and he does not lack anything, he has plenty of affection, but internally he suffers great frustration because he becomes aware that he cannot communicate and his speech codes are ruled by onomatopoeic sounds, as he does not articulate words to express himself except for a few very repetitive ones; it’s as if he exists in the world with only fifty sentences with which he fends for himself for anything. I started to think that the best way to create it was using an inner monologue, as if trying to express things and not being able to. When I go down the street and see a person with limitations accompanied by their relatives, it is the Ludovicos who inspire me. On the streets of Miami or anywhere in the world, when I see young and old drug addicts trapped in their mind-boggling hallucinations from which they cannot escape back to reality, I also see Ludovicos, ones who were not born like that but who were shaped by many circumstances of our modernity.

A Planetary Choreography: Each Tragedy Serves as a Screen to Hide Another

Camila Castaño

As a graduate of Florida International University (FIU) and holder of a Bachelor of Business Administration in Marketing and certification in social media and digital marketing analytics, Camila leads Book&Bilias. This business challenge is parallel with her growing work experience in other corporations. Camila commits to maximizing the potential of her father’s work by creating spaces for its current and future creation, ensuring its expansion in international markets and its application in areas such as dramaturgy with evolutions in film and theater.