The Sky Also Belongs to the Beggars

Autor: ©2025 William Castano-Bedoya

“THREE-MILE CHRONICLE”

This Sunday, under a rather chilly weather—unusual for these parts—I headed out early for my walk. At that hour, the country my eyes witness has not yet decided whether it will be a kind day or an indifferent one. I walked listening to classical music; all week I had walked to cheerful carrangas, and I wanted a different tone for the morning. Although my chronicles are usually three miles long, lately I’ve allowed myself to stretch the distance a little further, testing my own endurance. Curiously, today’s chronicle didn’t come from that walk, but from the moments that followed in the next hour—these days I dedicate my walks to solving the riddles of my new novel, one I’ll present before March of next year.

After finishing my route, I went to buy a hot coffee at a place I frequent, where people line up in pursuit of the same ritual. There is usually murmuring among them; I almost never engage, though that day I did briefly. Buying coffee takes just a few minutes—arrive, wait in line, head back home. I always bring a hot café con leche to my wife, a small tradition we’ve nurtured with affection.

On my way back, from the car, across the road, I saw a man sitting on a bus-stop bench on Bird Road, right between two giant pharmacies and surrounded by a few pretentious restaurants where, from time to time, I remind myself that I also inhabit a place where I can afford a pretty meal amid the casual ones of everyday life.

What caught my attention was that I hadn’t seen homeless people in my area for quite some time. The government had expelled them months ago—not only from my neighborhood but from much of the city. They were “an embarrassment,” declared the legislators who passed that law: the removal of homeless people from public spaces, feeding the narrative of public insecurity.

It moved me to see him struggle to stay seated. His movements were weak, very weak, his body bent forward as if it had given up holding him upright. I noticed a crumpled sleeper beside him and, behind some bushes, a blanket half-spread, trying to dry under the sun from the humidity of the early-morning dew.

I drove home in absolute shock. What a cruel reality for a human being.

I prepared a simple sandwich—toast, cheese, ham, mayonnaise—placed it in a Ziploc bag with a napkin and a mozzarella stick. I went back and approached him with some timidity, afraid he might reject me abruptly, but he didn’t.

I confess I feared he might be an undocumented immigrant, given the widespread stigma. But no—he was an older American man, white, with a thick beard, almost Christmassy. The perfect—terribly perfect—image of the Santa Claus from the old Coca-Cola commercials, but without December’s magic or the nostalgia of silent nights and holy nights.

And yet, when he lifted his gaze, I discovered something unexpected: a broken but living nobility. It lasted only an instant, but the association was immediate—not a religious Christ, but a human Christ, like those Christs in the movies: exhausted, beaten by life, yet still holding a clean, luminous gaze.

I stepped closer to examine him better, searching for his face and its hidden kindnesses: the lines of a suffering forehead, his exemplary beard. Oh, how I would love to have a beard like his. His battered human beauty struck me deeply.

And then came the smell first. Back home we call it berrinche: dry urine, days of street life, a kind of exhaustion you can smell. It didn’t repel me; it reminded me of the scent of poverty and abandonment I’ve known in other times.

I extended my hand. Something happened that I didn’t expect: he extended his without hesitation. His palm was soft, not rough. The hand of someone who wasn’t born on the street, someone who once had—perhaps still has—a home and a family, even if no longer a Christmas or the joyful noise of happiness.

He wasn’t a “beggar,” because to be one he would have to be asking for money, food, something. He was a man of the street. In our American vocabulary we call them homeless—people without a home.

A beggar—strictly speaking—is someone who asks for money. And so is a bad politician who asks for votes to reach power easily. A beggar is someone who lives by taking without offering empathy in return, someone who sells need disguised as charity.

But he wasn’t begging; he was simply trying to keep his body upright. He wasn’t drunk or high. I confirmed it when he thanked me for the sandwich. What possessed him was the cold morning light, which he perhaps wished to keep seeing after surviving the night.

He was a white American man who had fallen into disgrace, displaced by the prosperity that seems to bless only the prosperous.

I handed him the sandwich. He received it without dramatics. A shapeless line of mayonnaise clung to his thick beard like a white trace of empathy. He didn’t say anything else; he just kept eating with his beard marked by that slightly sweet, creamy taste of oil and egg.

I also offered him an electrolyte drink. I thought he might be dehydrated from the harsh use his body endures under such circumstances.

“I love you, man,” I told him. Not out of pity; it came out of me in the spontaneity of the moment. I couldn’t find another way to express solidarity. Then I stepped away, noticing how completely that bite had captured his attention.

Again, on my way home, shaken by having fulfilled so simple a task as offering food to a homeless man, I remembered the brief little pilgrimage we strangers formed minutes earlier in the coffee line. We were talking about why places feel so empty these days. Someone said prices are too high; another said people are afraid.

All I managed to say, joining that spontaneous conversation among strangers, was:

“There are a lot of people suffering in this country. And there are even more people happy because there are so many people suffering.”

I said it without knowing that minutes later I would see it reflected in my “friend” on the bus-stop bench.

That sentence kept circling in my mind through the morning. That’s why I dared to write this chronicle, free of philosophers, alter egos, or the usual reflections that accompany my walks.

I remembered that months ago the homeless were expelled from several neighborhoods. They were moved like someone shifting an old piece of furniture. No one asked where they would go, or where they would find the food scraps that keep them alive: now-cold greasy fries, half-eaten burgers, cardboard cups still capped with traces of sugary drinks.

They were pushed to the edges of the city: zones with no restaurants, no useful garbage, no shade, no bathrooms, no pretty people. Zones where hunger truly kills.

In my novel We the Other People: The Beggars of the Mercury Lights, I wrote about those who live under the cold mercury lights—those who never enter the official narrative of modern, “evolved” societies.

Today I understood that the lives of the unfortunate, the miserable of our societies, are not literary metaphors. They are discreet prophecies—living testimonies that drift between neglect and incomprehension.

A sentence I wrote long ago returned to me, never imagining I would one day see it embodied on a bus-stop bench:

“The sky also belongs to the beggars”.

Perhaps because the earth—at least this earth—belongs to them less and less.

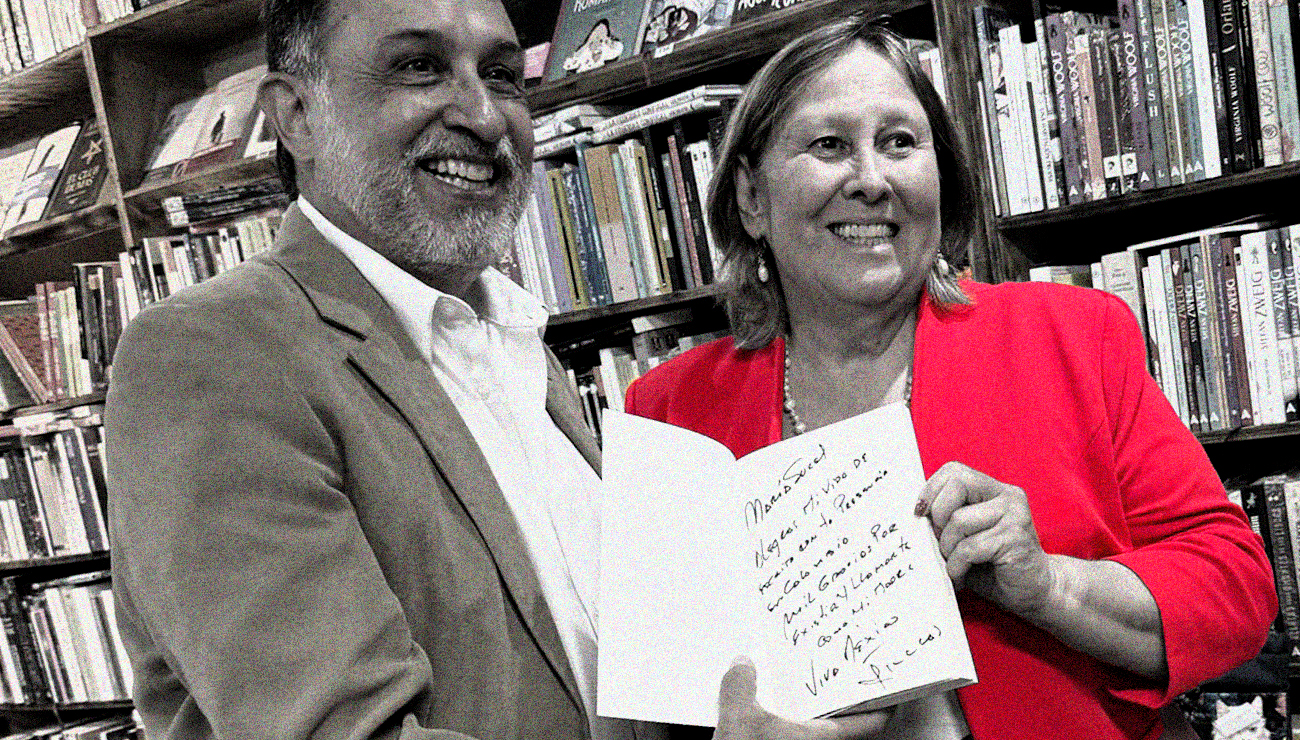

The image accompanying this chronicle does not correspond to the real face of the man I met today. Out of respect for him—for his discretion, his fragility—I’ve included a referential image, one very close to his appearance, so that you, dear reader, may picture him without violating him.

A Planetary Choreography: Each Tragedy Serves as a Screen to Hide Another

William Castaño

William Castaño-Bedoya is an American writer based in Coral Gables, Florida. His literary fiction explores the ethical, psychological, and emotional structures that shape human relationships, focusing on love, vulnerability, and the tensions between power and compassion. His narrative voice is marked by interiority, silence, and moral inquiry, privileging emotional intelligence over spectacle. After a long career in marketing and creative leadership, he turned fully to literature, bringing a strategic understanding of contemporary human experience to his work. He is the author of several novels, including "The Intriguing Stillness of the Tides", "We the Other People", "Ludovico", "Flowers for Maria Sucel", "The Galpon", and "We’ll Meet in Stockholm".