Habeas Corpus and the Stigmatization of Immigrants

Autor: ©2025 William Castano-Bedoya

“THREE-MILE CHRONICLE”

These past weeks my walks have been accompanied by an insistent thought: the persecution and deportation of immigrants. I am not referring to criminals, who are few compared to the universe of millions; I am thinking of ordinary people, of those who silently sustain this country, shoulder to shoulder with all ethnicities: Americans of ancestries from Europe (most of white American citizens), Latin America and the Caribbean, Asia, Africa, Australia, and so many others who coexist in this great fused nation. The woman who serves me a cortadito with its bittersweet taste at the corner café, the sturdy though thin and sweaty man who cuts my lawn under more than one hundred degrees of heat that scorch his back, the politician who represents my civic interests—here, in the state, or in the nation. I have never asked any of them if they are legal or illegal.

I recall a conversation with a good American friend, a white man, about this very subject. Part of that exchange becomes today’s chronicle. He put it with simplicity and clarity:

Reflections of a White Man: 143 Latinos per 100,000 — Far Too Few for an Ethnic Stigma

Walking through certain streets in the United States and witnessing how Latinos are treated seemed to this white man born here like attending the silent delivery of a sentence without a trial. No one reads the charges aloud, yet the verdict is already written: in campaign speeches, in alarmist headlines, in algorithms that sustain prejudice. In this narrative, the suspect always has an accent, the threat supposedly comes from the south, and the word “security” has become a polite way to exclude.

Yes, there are gangs. Yes, there is violence. Yes, there are crimes committed by people of Latino origin. But the dangerous falsehood lies in building a narrative around those exceptions to stigmatize an entire community. The exception does not define the group—unless it is not your own.

According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, the incarceration rate for Latinos is 143 per 100,000 people—comparable to, or even lower than, that of non-Hispanic whites, at 155 per 100,000. Studies by the Cato Institute and Pew Research Center show that immigrants commit fewer violent crimes per capita than U.S.-born citizens. Yet such facts rarely make it into campaign ads.

To put things into perspective: out of the 174 million citizens eligible to vote, the 77 million who elected the president represent about 44%. And when measured against the total population of 335 million, the proportion is roughly 23%. The numbers do not lie: it was a minority that chose to stigmatize immigrants as criminals, and yet that minority managed to impose its echo so that the Executive could enshrine cruelty in the name of the entire nation. These 77 million voices became the chorus of a message that targeted Latinos as the main object of stigmatization, almost as if they were a Hamas faction within the United States. The irony is that within those 77 million were also some 8 million Latino-Americans who applauded their own self-stigmatization. They voted in expectation of handouts or a false existential salvation, but their calculations proved imprecise: what they embraced as acceptance ended up branding them as suspects. And most disconcerting of all is that even Latino-American elected officials now watch in astonishment as this turn unfolds: they no longer know whether they stand with the persecuted who resist, or with the executioners. An uncertainty that, without doubt, will weigh heavily on them as the next elections approach. Surely, many will chase handouts rather than votes.

Meanwhile, the dominant narrative suggests that protecting the country means stopping the arrival of Latinos. Do it, stop that arrival if you consider it necessary, but do not attack Latino-Americans with suspicion or with identification papers that brand them as bad people. Legalize that loyal, constant, and unconditional workforce, and the country would have greater stability and less fear. And, surely, the hatred of others toward Latinos might begin to subside.

To claim that Latinos are a threat because of 5,636 arrests—out of a population of more than 65 million people of Latin origin—is like trying to extinguish the sun with a glass of water. That figure represents only 0.0086% of the population of people of Latin origin. Yet instead of highlighting that number, the opposite is repeated endlessly: that they come to harm us, to bring crime, to collapse the nation. A lie, when it serves a political purpose, needs no logic. Only repetition.

Because being Latino-American means being a senator of the republic, whether born here or not. It means being a newly appointed Secretary of State, a city mayor, a doctor in public or private hospitals, the spouse of a global leader, an elite athlete, or a soldier in the U.S. Army. It means being a NASA astronaut, an engineer in Silicon Valley, a professor at Harvard, or a scientist in cutting-edge labs. But it also means being a landscaper, a bartender, a cleaning worker, a cook, a rideshare driver, a nanny, a roofer, a painter. There is not a single city, economy, or success story in this country that does not have a Latino-American behind or in front of the curtain.

Let it be clear: Latino-Americans are not the problem. They are part of this nation, not a fragment. They have been here for centuries, fought its wars, built its cities, and nourished its culture. They are no longer only the children of Latin America: they are, in many cases, more children of the United States than of the lands from which their grandparents came. Millions of them were born here, grew up here, and built their lives here. And yet, under current conditions, they live under the persecution of stigma. The wrongful arrests of citizens shout it out loud.

Because if we imprison Latino-Americans simply for existing, but pardon those who manage cruelty for their crimes, we are not talking about justice: we are talking about privilege. And privilege, when normalized, ceases to be invisible. It becomes the open wound of our democracy.

At the end of today’s walk, I thought habeas corpus was born to remind us that the human body cannot be seized by power without trial. But in these times, that principle seems to fade into speeches that normalize suspicion. And so, every Latino-American who walks these streets carries on their shoulders not only the weight of their own life, but the unjust burden of a stigma.

Perhaps my steps today will not change the politics of a nation. But at least they remind me that dignity, too, is walked: three miles a day, against the wind of selective cruelty.

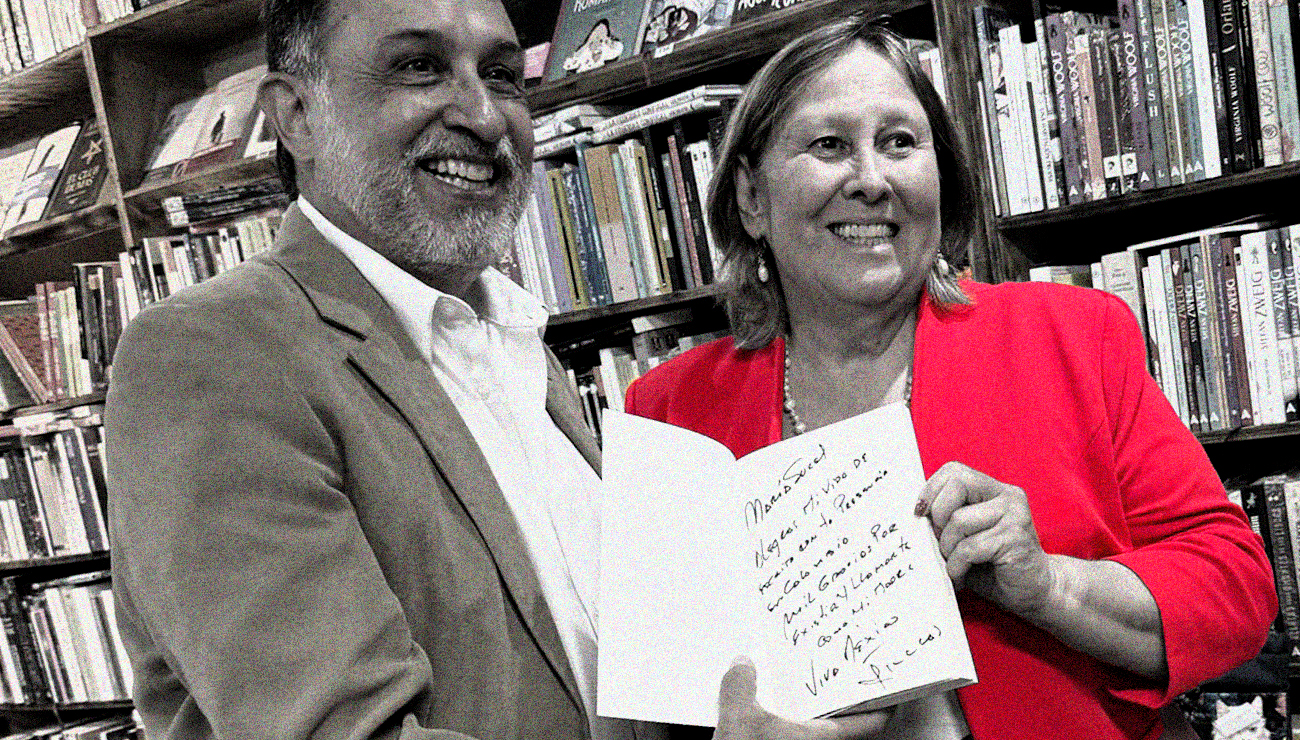

¿Te quedaste con ganas de más? Tu próxima historia favorita está a solo un clic.

¡Explora mis libros!

A Planetary Choreography: Each Tragedy Serves as a Screen to Hide Another

William Castaño

William Castaño-Bedoya is an American writer based in Coral Gables, Florida. His literary fiction explores the ethical, psychological, and emotional structures that shape human relationships, focusing on love, vulnerability, and the tensions between power and compassion. His narrative voice is marked by interiority, silence, and moral inquiry, privileging emotional intelligence over spectacle. After a long career in marketing and creative leadership, he turned fully to literature, bringing a strategic understanding of contemporary human experience to his work. He is the author of several novels, including "The Intriguing Stillness of the Tides", "We the Other People", "Ludovico", "Flowers for Maria Sucel", "The Galpon", and "We’ll Meet in Stockholm".