A chat with Gustave Flaubert that started from my garden

Author: ©2024 William Castano-Bedoya

THREE-MILE CHRONICLES · Reflections on Literature and the Human Condition.

I was contemplating how to approach Gustave Flaubert through my thoughts, so I proposed a meeting to him last Monday—right in the garden in front of my house. I suggested that he accompany me on one of my walks along the eastern route, the one I frequent the most, and he agreed. The appointment was at seven in the morning, taking advantage of the coolness of the day that wouldn’t affect Flaubert too much with his nineteenth-century attire. And so it was.

Five minutes to seven, I was alerted by the sound of the hooves of a Breton equine with reddish-brown fur, thick mane, and intelligent gaze, giving it an air of rusticity and nobility. This horse pulled a calèche; a light carriage from the nineteenth century, with a single seat, simple yet elegant, with a folding hood that could protect Flaubert from the sun and rain.

The requirement to arrive in a calèche was a condition imposed on me because he confessed that he didn’t know how to handle vehicles, not even how to ask for a public service car. I couldn’t help but say that whatever he proposed was fine; after all, he had been traveling since time immemorial, since 1857, in his eagerness to promote his recent literary work in those years. I’m referring to ‘Madame Bovary.’ He also sought to justify his novel in other times, as it was initially subject to censorship and legal challenges due to its realistic portrayal of adultery and perceived affront to social norms. However, it is known that Flaubert was ultimately acquitted, and his novel became a cornerstone of French literature.

I saw him get out of the calèche, which disappeared after the coachman got down and closed the small door. I was impressed to see him descend, twirling the tip of his handlebar mustache, a thick and prominent mustache with tips curved upward, extending beyond the edge of his lips. A voluminous mustache often associated with literary figures, artists, and gentlemen of the Victorian era. This style gave Flaubert a distinctive and recognizable appearance, in keeping with his image as an intellectual and literary figure of his time. Flaubert observed the neighborhood with curiosity, perhaps comparing it to his time. I watched him closely, still surprised to have him there. Émile Zola described him perfectly: “Flaubert is a giant of a man with a leonine head, a great mustache, and a booming voice. He had the appearance of a Viking, with a powerful body and a rough and cordial manner that belied the sensitivity and refinement of his prose.”

Then, determined, I opened my door and went out to greet him with open arms. Seeing me, he smiled and asked me in jest:

“Do people still walk in this era? I see that everyone is lazy, moving at speed sitting in their cars.” I explained to him that modern cars are like motorized calèches, invented by Carl Benz in 1886. Then, I changed the subject to a more serious matter: femicides.

“Uhm,” he replied jokingly, “— so these cars appeared a few years after I bid farewell to human life,” he added resignedly to his own comment.

“We began our walk, and my main interest was to explore topics related to femicides. During our conversation, I mentioned the modern concept of ‘femicide,’ but Flaubert pointed out to me that in the time of ‘Madame Bovary,’ such a term did not exist. Violence against women was mainly considered private or domestic matters, and rarely received adequate public or legal attention, despite the tragic events that occur in the novel, such as Emma’s death.

‘Women had few legal rights and were subordinate to male authority, whether of the father or the husband,’ he affirmed. — ‘Justice was patriarchal and tended to be lenient with men who committed acts of violence against women.’

‘One must understand the path of time,’ I said, ‘— you see, nowadays, the term “femicide” is used to describe the murder of a woman for reasons of gender, thus recognizing the systematic component of violence against them.’

‘Uhmm, well, femicide, as understood today, was not a concept in the time of “Madame Bovary,”‘ Flaubert affirmed, ‘— however, crimes that would fit this definition did occur, occurred frequently although they were treated very differently by the society and legal system of the time.’

‘What motivated you to write ‘Madame Bovary’ if your goal was not to defend the cause of women in history?’ I asked him.

‘Several reasons,’ he replied, ‘— both personal and artistic factors. I was overwhelmed by a great personal dissatisfaction; I was disillusioned with the mediocrity and materialism of the bourgeois society of my time. “Madame Bovary” is a critique of bourgeois values and the hypocrisy of the rural middle class. Through the character of Emma Bovary, I satirized the superficial aspirations and dissatisfaction that prevailed in bourgeois society.’

‘How much realism is there in your literary fiction?’ I asked him.

“Realism?” he replied, “— well, you see, I wanted to explore the human condition in a realistic and objective way, without idealizations. Through Emma Bovary, I portray the internal struggles and frustrations of a woman trapped in a provincial life. I have been concerned with the psychology of the individual and how personal desires and aspirations can clash with reality and lead to disillusionment and tragedy.”

Flaubert paused and came up with his own questions: “You told me that you are a contemporary writer. Have you written anything related to women? I see your interest in that topic.”

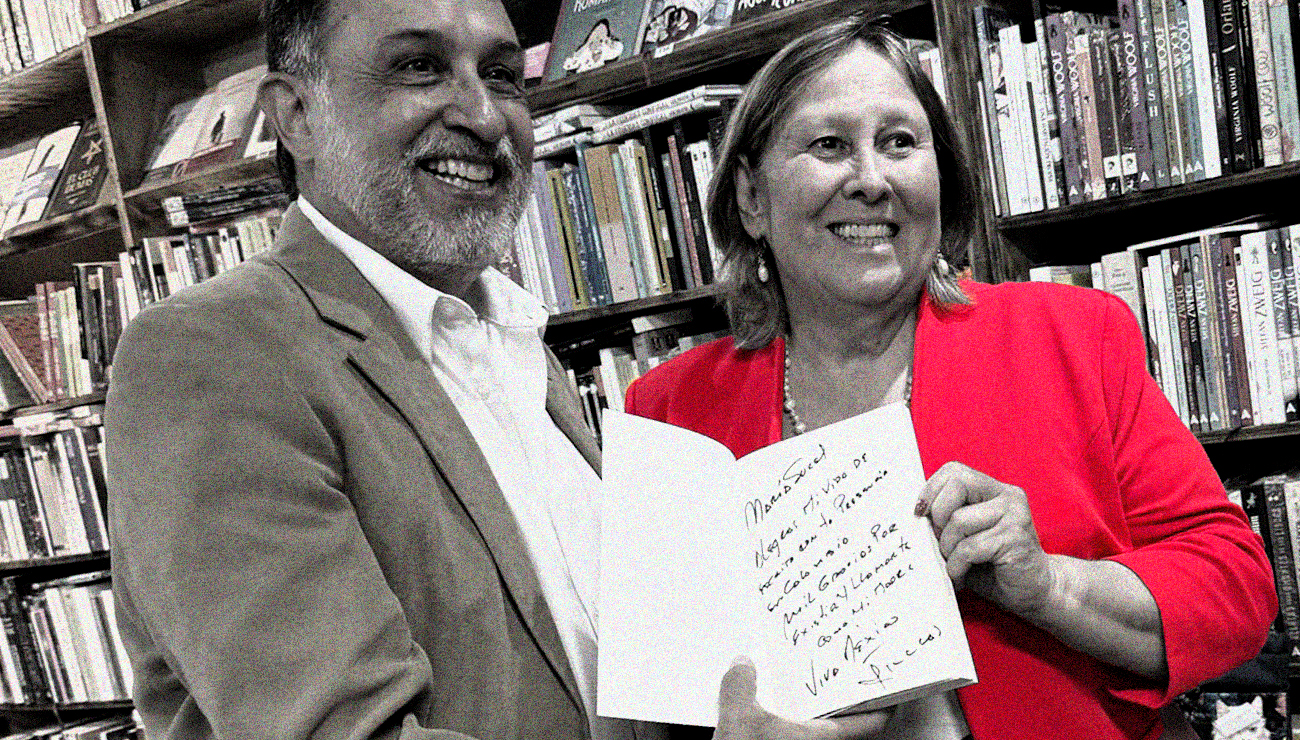

I felt shy to tell him that I write, and that, nevertheless, he is a master compared to me, so I dared to speak of myself: “Well, you see, my first novel was written thinking of women, inspired by the life of my mother, a woman who died in life and who, despite her strength, never managed to unite her body with her soul. It was called ‘María Sucel.’ She was pursued by flowers throughout her existence. Let me tell you the last paragraph of that novel, it says: ‘Silence reigns in the funeral home. The door opens, and the flash of light bothers the sight of those who turn to look. It is a messenger with a crown of tuberoses that someone has ordered. The messenger exclaims: — Flowers for María Sucel!”

“Does she die?” Flaubert asked me.

“Yes, she dies just like Emma,” I replied sorrowfully. “She dies in the midst of great disillusionment and sadness. María Sucel gives up being an adulteress for the love of her children and decides to live with her husband, both sharing a accompanied solitude that lasts for decades. Emma, however, dies after being an adulteress by her own decision.”

“Wow, what an interesting analogy, I wouldn’t have thought of making those parallels, in ‘Madame Bovary’ I focused aesthetically on staging adultery in a time governed by the masculinity of fathers, husbands and siblings in many cases.”

“That’s something I noticed through the reading of your novel. What were your literary commitments?”

“I was committed to ‘art for art’s sake’ and sought stylistic perfection. In ‘Madame Bovary,’ I demonstrated attention to detail and innovation in language use, aiming for an impersonal and objective narrative. Inspired by dissatisfied women, I captured their struggles and aspirations through characters like Emma Bovary.”

“There was a prevalence of romanticism in your time, how did you fit in there?”

“I wanted to differentiate myself from romanticism, which focused on emotion and subjectivity, opting for a more objective and dispassionate approach.”

“In your own words, tell me about Madame Bovary.”

“Madame Bovary is the wife of Charles Bovary, a rural doctor. The novel explores her dissatisfaction and desperate quest to escape her reality, leading to financial and social ruin, and ultimately, to her tragic end.”

“Tragedy accompanies great literary works. Emma Bovary constructs a disastrous and painful destiny: her financial ruin, extramarital affairs, and inability to face reality lead to her tragic end. I want to congratulate you on your meticulous prose and your ability to represent Emma’s internal struggles realistically.”

“You speak of my prose? What do you see in it?”

“Your prose is a testament to your skill and dedication to literary art. Your meticulous style and linguistic precision create a rich and impactful narrative.”

“I greatly appreciate your perception.”

“I like it when you use meticulous descriptions to create a vivid image of everyday life. That contributes to the realism.”

“I adopt an impersonal and objective approach, maintaining emotional distance from my characters. I present their actions and thoughts neutrally, allowing readers to draw their own conclusions.”

Then, he spoke about his narrative technique, the precise choice of words, his social critique, and implicit irony.

“In the novel, I can notice your obsession with the precise choice of words,” I commented. “— I imagine you spending long periods revising and perfecting your prose to ensure that each word conveys exactly what you desire.”

“That’s just the craftsmanship of writers, don’t you agree?” he exclaimed.

“In social matters, you don’t neglect,” I added, “— you write so that two centuries later, those who read you understand the present environment of your existence. I see you use irony to criticize bourgeois society and Emma’s romantic aspirations.”

“That irony is often subtle and manifests through the disparity between the characters’ illusions and reality,” he told me, “— and, although the prose is objective, the detailed descriptions and implicit irony reveal a sharp critique of the hypocrisy and materialism of the society of his time.”

“I would like to hear from your lips the answer to this question, pay attention: what do you think was fundamental for your prose to mature to the level of the masters, even though you were born with that overwhelming talent?”

“I believe it must be the fact that I explore the internal emotions and desires of my characters with great depth. I tried to express the complexity of Emma Bovary’s thoughts and feelings accurately; I wanted the reader to understand her psychology.”

“Are you feeling tired?” I asked him.

“Tired?… of what?” he replied, “— I’m having a great time.” He responded, shrugging his shoulders and offering me the palms of his hands.

As we returned, I took the opportunity to talk to him about a novel by Gabriel García Márquez, “Until August.” Surprised, he asked me who Gabriel was. I explained that he was a Nobel Prize winner, one of the best. He commented that the prizes were founded after his death and added: “I would have liked to meet García Márquez. Tell me about him.”

I replied, comparing them, affirming that both are literary giants, and suggested that García Márquez may have been inspired by “Madame Bovary.” I explained:

“‘Until August’ and ‘Madame Bovary’ have differences and similarities in style, themes, and character treatment. García Márquez, known for his magical realism, uses a lyrical and poetic style with rich descriptions. Although ‘Until August’ is more realistic, it maintains elements of this style and uses an intrusive narrator. In contrast, you, Gustave, are the master of realism, with detailed and precise descriptions of everyday life and an impersonal and dispassionate style. The protagonists of both novels are dissatisfied with their lives and seek something more, although their contexts and motivations differ. ‘Until August’ explores desire, nostalgia, and personal rediscovery, while ‘Madame Bovary’ deals with Emma Bovary’s dissatisfaction and her search for escape through adultery, leading to a tragic end.”

The walk concluded upon arriving at my home. The calèche was patiently waiting for Flaubert. He did not accept my invitation to enter the house, mentioning that he had another appointment related to the history of his novel. Thus, we ended our meeting, speculating on various topics. For me, it was a true pleasure to receive such a significant visit and walk with him. Above all, it was important to highlight female figures as inspiration and fundamental beings of life, unjustly fighting for equality. Although they enjoy freedom of thought from the moment they become conscious, I hope that someday they can also fully enjoy the freedom of their actions.

A Planetary Choreography: Each Tragedy Serves as a Screen to Hide Another

William Castaño

William Castaño-Bedoya is an American writer based in Coral Gables, Florida. His literary fiction explores the ethical, psychological, and emotional structures that shape human relationships, focusing on love, vulnerability, and the tensions between power and compassion. His narrative voice is marked by interiority, silence, and moral inquiry, privileging emotional intelligence over spectacle. After a long career in marketing and creative leadership, he turned fully to literature, bringing a strategic understanding of contemporary human experience to his work. He is the author of several novels, including "The Intriguing Stillness of the Tides", "We the Other People", "Ludovico", "Flowers for Maria Sucel", "The Galpon", and "We’ll Meet in Stockholm".